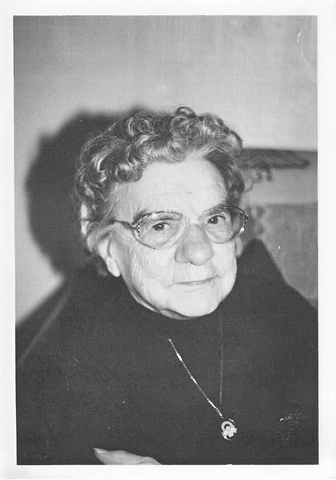

Before to proceed backwards, me, Alice Tetrault (Jacques Boulerice)

Her name was Alice Tetrault. Between the age of two and fourteen years old, she was named Alice Menard. Later on, she was called Alice Boulerice. In the family we simply called her Little Alice.

On a day in November 1998, she started to write about her life. She told me she wanted to start writing before starting to « depelotonner », before the thread of her life unfolds in reverse to the beginning of her life, empty of herself. She got Alzheimer and she knows it. Tomorrow, she won’t.

Therefore, she asked me to read her what she writes, what she carefully noted on the sheets of an old ring binder. I found there words and dates that she wants to save from forgetfulness the main events of her life. The good as well as the bad. She also asked me to note what is going to happen to her, about what we will be going through, together. She didn’t know Alzheimer would spread over more than ten years and make her revisited her life. Me too.

I mainly used my notes and hers to write her story in La Mémoire des mots (at the edition Fides). On ther words, I continued what she started: telling her days up until the last one, when the sickness stopped her.

When Josee Tetreault asked me to write a biography of my mom for the ADLT newspaper, I immediately wanted to tell it from Little Alice’s perspective, Alice Boulerice, Alice Menard and finally Alice Tetrault. The following pages are sort of an unauthorised biography. Her, who always wanted to « to her part in helping people » won’t mind it.

These are her words:

On October 24, 1918, mother died following the Spanish flu. Her name was Leonida Boily. I was nine months olds. I’m born in January 20, 1918.

Me, Alice, stayed in Montreal with the neighbour, Mr. Menard and his wife Parmelie. My brothers and my sister were sent to family member in the country-side but not me. There was no place for me there. I became Alice Menard.

Mrs. Menard died on December 3, 1921 in the parish of Sainte-Philomene de Rosemont. I was three and for the second time, I had lost my mother.

We then moved to Saint-Hyacinthe, in pension in a family named Cadorette. Then, Mr. Menard married Angele Major on May 15, 1922 at Saint-Hyacinthe. I had a third mother. I just turned four on January 20, 1922.

Mr. Menard was still working for the city of Montreal. On Sunday night, we would escort him out to the train station. Before leaving, He would say to mother Angele to not let me play outside with the other kids. He was afraid my real dad, Eugene Tetrault could try to kidnap me.

Mother Menard was really nice and patient with me. She would let me play with the other kids. When Mr. Menard would come home on Saturday a neighbour would tell him and he would get angry at Angele and hit me. It was like that every weekend. My father Eugene had learned he was hurting me.

During the winter 1923, Mr. Menard bought a land in Saint- Jude in the Michaudville lane. Before Christmas, we moved in with a horse, an old car and some cleaning. It was an old house and it was cold.

When September came, I went to school. It was far, but in the evening I was happy about my day. The next day I would leave again with my lunch: buttered toast with brown sugar on it. When the snow came I stopped going to school. All winter my mother would teach me catechism. For fun I had my dog Bijou to play and talk to.

At night, we had to get the wood in to warm the house. We used to sit around the stove. I would put my feet in my dog’s fur. At night, he would sleep at my feet to keep them warm. He was also protecting me.

When summer was there I would cry every morning to go back to school. But it never happened. Mr. Menard needed me to work so I did about a year of school bit by bit. It wasn’t much.

We didn’t have much to eat. Mrs. Menard would hide food for me.

One day, my mother’s sister, my aunt Almeria, came from the States to see me. But Mr. Menard learned about it and sent me to Saint-Dominique so we couldn’t meet. After her visit my aunt started sending me gifts for holidays: a doll, a beret and candies. When it was candies Mr. Menard would eat them all or give them to the dog. He was good at making me sad.

One day, I was ten, it was in 1928. Daddy Eugene, my sister Marie-Rose and my brother Paul visited me in Saint-Jude. It was the first time I saw my dad in a long time and the first time I ever saw my sister and my brother Paul.

Years passed.

In the summer of 1934 the neighbour told me: « why don’t you write your father to come pick you up? » They gave me two stamps of two cents, I wrote and mailed my letter. So, in August I believe, when I came back from church (Mr. Menard didn’t go because it was too far for Mrs. Menard), my father Eugene Tetrault was waiting for me with my sister and my brothers Paul and Adelard. I was sixteen.

I finally got away from it. It was hard, but I left later on with the driver bringing cream to Saint-Hyacinthe. I found myself at my grand-father Israel Tetrault’s sister.

A new day started for me: good food, a family and a car to go to church every Sunday, it was almost paradise.

The same year, in Montreal, I worked as a maid for Madame Hector Authier. This woman lived alone on De Lorimier Road, between Marianne and Rachel. 2.50$ by week, the food was provided.

In the spring 1935, the whole family moved on a farm in Saint-Leonard d’Aston. I was working in town and helping on the farm.

In 1939, we sold the land and I found work as a seamstress in Yamaska Garment in Saint-Hyacinthe. I worked there from September 1939 to April 1943. I loved working there and made lots of friends.

In April 1943, my friend Claudette Brule and I decided to go work at Dominion Bridge in Lachine. We learned to solder boat hulls. It was war and we did our part.

Alice making her war effort (upper right)

On the night or May 9, 1943, a Wednesday, my friend Claudette asked me to follow her to the Bonaventure’s train station to see her fiancé , Paul Brodeur, who was going back to military camp in Halifax with his friend Urgel Boulerice. I still see him with his army bag on his shoulder. Paul presented him to me. He asked me if I wanted to write to him. I said yes. I knew he was mine.

After that it went fast. I was in love over my head. We saw each other 5 times. The fifth time was June 10, 1944; it was our weeding day at the Saint-Sacrement de Lachine’s church. I have never regretted it.

From there, I followed Urgel to Sussex, then at « Long Branch » in November 1944, near Toronto, before coming back to Halifax. After the 1945 Holidays, he was transferred to the Lauzon camp. We stayed at Mrs. Leontine Belanger’s house until the end of the war on June 21, 1945. I was seven months pregnant.

We came back to Saint-Jean and on July 9th, Urgel resumed work at the forge of the Singer factory. We are both happy. The baby is on its way. We can’t wait.

On August 21, 1945, a Tuesday around noon, a big boy of nine pound and thirteen ounces is born. After leaving with my parents in law, then renting a room, we moved on October 1st, 1945 in a nice small apartment on the Laurier road in Saint-Jean. Finally home! Mine, for the first time in my life, I was in my own home.

These were good times. We bought a house on Frontenac road. We worked a lot. We had a lot of parties with from both Tetrault and Boulerice family’s side.

Urgel Boulerice and Alice on their wedding day

In 1974, Urgel retired from Singer. We got a small piece of land in l’Acadie. Urgel would build his cabin there and we would make a big garden. Jacques teaches in a cegep. We are the happy grand-parents of two small boys Alexandre and Nicolas. The days are good, but the time had passed.

I February 17, 1974, my aunt Almeria died at Saint-Marie in Bauce. I went to her funerals. She hadn’t forgotten me when everyone did.

Father Eugene, (son of Israel Tetrault and Julie Langelier) died in October 18, 1976 at the age of 87.

On July 10, 1984, Urgel goes under surgery for his cancer. He died in February 14, 1986. It’s Valentine Day, the lover’s day. That man brought back my childhood, I was happy with him. The house got empty, so did my heart. Thankfully there still was my grand-children, the choirs, music and friends. Life goes on.

Now Alice isn’t talking anymore, I am the one speaking. She will only add about two to three pages to her note book. Some lines to say how in December 15, 1986 she bought a piano, an old dream in black and white to give some colour to her widowed life. She took piano classes with her grand-kids Alexandre and Nicolas. Happiness played its way back in her life.

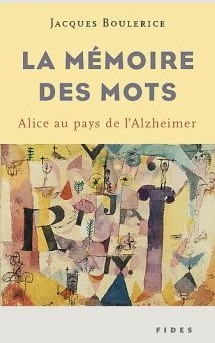

On my side I followed Alice’s advice. I took notes about her late days and the sickness, about childhood and love. I collected insightful reflections for over ten years. The end of the story, her story, is in this book I owed to her: La mémoire des mots, Alice au pays de l’Alzheimer, Biblio Fides, Montreal, 2015.

An epilogue tells the last days of my mother. Not Alice Menard, nor Alice Boulerice, but Alice Tetrault, the one who got the last word.

References

Ce livre raconte l’aventure unique d’une femme qui fait un pied de nez à l’oubli et à l’Alzheimer. Pendant plus de dix ans, elle élabore une stratégie instinctive et passionnée pour s’accrocher à la joie d’être présente en dépit de tout. À travers ses égarements, cette maman autodidacte apprend à son fils écrivain quelque chose d’essentiel sur le pouvoir des mots et sur le métier de vieillir. «En 1999, je commençais à prendre des notes à partir des propos de ma mère qui perdait de plus en plus ses repères. Au départ, je savais que sa vie allait lentement se vider d’elle-même. C’est un terrible chemin de croix. Mais je ne devinais en rien la profonde et salutaire communion qui nous attendait. Tout ce qui reste n’est pas destiné au vide ou à l’oubli.»

Fermez les yeux. Plongez dans vos souvenirs d’enfance. Il y a fort à parier que vous reverrez une petite voiture en bois de marque CCM qui ressemble à celle qu’évoque Jacques Boulerice dans ses chroniques. «Jambe pliée, écrit-il, genou droit au plancher de la voiture de mes huit ans, le pied gauche bien posé sur le sol et la main sur le timon de la caisse (mon père disait “la togne”) je me prépare à sortir de la cour du 375 A, rue Laurier à Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, tout comme de l’été 1953. Je ne vais plus m’arrêter.» Ce livre parle d’instants de bonheur vécus au quotidien. Il en parle comme seul un poète sait le faire. Sous sa plume, les mots prennent vie et nous enchantent. «Avec cette voiture apparaissent les lieux où elle passe, les saisons qui l’ont usée, l’enfance qu’elle promène et tout ce que la vie y accumule depuis plus de soixante ans. Attaché aux ridelles, s’accroche la curiosité de voir ce que demain y fera monter, tous les clins d’œil du bonheur qu’on espère et qu’on invente au besoin.» Poète, chroniqueur et romancier, Jacques Boulerice est l’auteur de plus d’une vingtaine d’ouvrages.