Our Patriote Ancestors (par Geneviève Tétrault)

The dawn of the 20th century was a turbulent period everywhere in the world. We need only consider the American and French revolutions which inspired the propagation of liberal ideas everywhere in the West, and the movement to decolonize the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in South America. Lower Canada was no exception to the rule. Inspired by its neighbor to the south, it too pursued a revolutionary route. Was it a class struggle or an ethnic one? What part did the descendants of Louis Tétreau play in these events? We shall see.

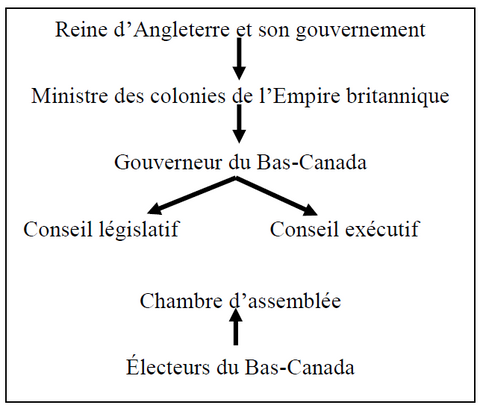

The Constitutional Act of 1791

Canadians first experienced the parliamentary system after the first election that took place in 1792. Freshly elected, the delegates from Lower Canada, a majority being French Canadians, were already arguing with their British colleagues over numerous issues such as the language to be used in deliberations, and the management of finances.

Whereas, at first, the delegates were independent, they would soon regroup in two parties, the British party and the Ca-nadian Party (which became the Patriot Party in 1826), names which leave little doubt as to their composition! The members of the British Party came mainly from the business middle class and were generally on the same wavelength as their countrymen from the Legislative and Executive Councils. On the other hand, the Canadian Party came from the liberal middle class that were the elite in the manors of the Saint Lawrence and Richelieu valleys.

Conflict in the Legislative Assembly

Very early, the limits of this facade of a democracy started to appear. In reality, delegates who represented the people in the Legislative Assembly had no power over the governing of the colony. The latter was always, in fact, controlled by London by a governor and his council. Before becoming law, a bill had to be adopted by a majority of the delegates in the Chamber, a majority of the Legislative Council (the equivalent of the present day senate) and sanctioned by the governor. What presented a problem at the time was that the governor and his council were appointed by and ruled in the interest of England. The British, then, always had the last word, modifying or refusing to adopt the proposals issued by the Legislative Assembly. Alternately, the king could veto the laws adopted in his colonies. As an illustration of the conflict between the elected Chamber and those appointed to the parliament of Lower Canada, we know that from 1822 to 1836, the Legislative Council rejected 234 laws proposed by the Legislative Assembly, almost half of the bills proposed. This situation became unacceptable for the patriotic delegates who demanded justice, freedom and a democracy with real power. That which elsewhere might be perceived as conflict between social classes, the middle classes against the nobility and the monarchy, turns out here to be an ethnic conflict because the elected delegates who opposed those who represented London were essentially French Canadians, whereas the others were essentially British.

The 92 Resolutions

In 1834, the delegates of the Patriot party drafted and expedited to London a famous document called the "92 Resolutions." After reminding the British of their loyalty to the crown during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, the French Canadian representatives demanded some major changes in the political and judicial functioning in Lower Canada.

They wanted, among other things:

- responsible government1

- an elected legislative council

- control of public funds by the Legislative Assembly

- a recognition of the French reality in Lower Canada with corresponding rights.

They denounced abuses of power by the British authorities and by governor Aylmer himself, the corruption, the double standard applied to French Canadians, the unfair way that justice was applied, etc. The document was adopted by the Legislative Assembly on February 21, 1834 by a vote of 53 for and 20 against. It was presented to the electorate for the October-November, 1834 elections and received overwhelming approval by the French Canadians who elected 78 patriot delegates out of a possible 80. Under the title "93rd resolution," the Chamber chose not to vote in a budget for Lower Canada until London responded to their demands. It took them three years to do so.

Meanwhile in the manors

After the British conquest, the governors were instructed to develop townships according to the English way of distributing and governing lands. There was, therefore, no longer any question of granting manors. In spite of this, the old system would last until 1854 and the majority of the French Canadians would live by it, encouraged by their Church to have as many children as possible. Thus, the population grew, but the available area of tillable land remained constant. Add to this several years of weather not favorable for agriculture, famine spread in the manors between 1833 and 1836. This famine coincided with a serious economic crisis that equally affected the United States.

While life was very difficult for the French Canadians, it was even worse for the Irish who landed by the tens of thousands at the port of Quebec, bringing cholera with them. These poor immigrants unleashed two epidemics (1832 and 1834) which resulted in more than 10,000 deaths, mainly among the French Canadians who would easily accuse the British government of deliberately provoking these epidemics to get rid of them. The popularity of the British authorities reached an all-time low.

The Two Solitudes

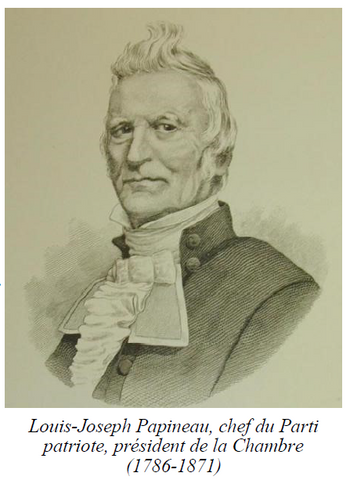

Louis-Joseph Papineau, leader of the Patriot party and president of the Legislative Assembly informed of the Russell Resolutions, the response to the "92 Resolutions" that were seen as a provocation. In fact, in addition to rejecting all of the demands of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, Russell gave additional powers to the governor who could now draw at will from the treasury without the approval of the Chamber. This is the context in which governor Gosford dissolved the Chamber in August of 1837.

Les Patriotes de 1837

- Present at the Saint-Ours Assembly on May 7: Pierre Tétreau (he seconded one of the resolutions)

- Present at Camp Saint-Denis: Jean-Baptiste Tétreau did Ducharme

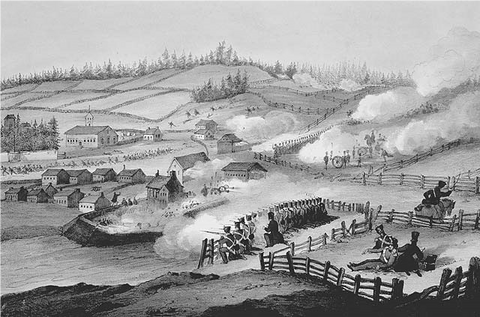

- Present at Camp Saint-Charles: Jean-Baptiste Tétreau and Benjamin Tétreault did Duharme (he was armed and very active; he participated in the battle of November 25)

- Present at Camp Saint-Mathias: Jean-Baptiste Tétreau (leader of a hundred men)

- Present among the patriots at Saint-Césaire in November 1837, they prepared for a surprise attack against the Brit-ish troops returning from Saint-Charles towards Chambly: Léon Tétreau did Ducharme, Dominique Tétreau, Timothée Tétreau, François Tétro son, Joseph Tétro son and Toussaiant Tétro father.

- Imprisoned in 1837: Saint-Luc Tétreau on November 22 as he was fleeing towards the United States at the head of some thirty men) and Jean-Baptiste Tétreau

- Relieved of their commission as captain or officers in the militia: Hyacinthe Tétro (2nd Rouville Battalion), Jean-Marie Tétro (1st Chambly Battalion)

It is from the United States where numerous patriots had sought refuge that the uprising of 1838 was organized. These folks were disgusted with the way Colborne had repressed the patriots in 1837. They founded a secret society of Hunter Brothers and they woite the declaration of independence of Lower Canada. During the night of 3 to 4 November, 1838, they crossed the American border to join their members of Lower Canada at Napierville. Even though they were better organized than the groups in 1837, the Hunter Brothers were held in check by the Volunteers2 About 1,000 persons were made prisoners, 108 were put on trial, 58 were deported to Australia and 12 were hanged in front of the prison in Montreal.

Attack on Saint-Charles, November 25, 1837

The Patriots of 1838

- Present among the patriots at Napierville in the fall of 1838: Pierre Tétreau

- Present with Robert Nelson, the leader of the Hunter Brothers, at Napiervile in the fall of 1838: Jean-Baptiste Tétreau (he initiated the Hunter Brothers into a secret oath and a secret password)

- Arrested in 1838: Jean-Baptiste Tétreau and Michel Tétreault dit Ducharme

- Imprisoned: Édouard Tétro did Ducharm

In the United States

- Anseme Tétreault sought refuge there. He was indicted by an American court for violation of neutrality after having set fire to a barn belonging to a loyalist3. He was later exonerated by a jury sympathetic to the patriot cause.

- Participated in the mayhem and pillage of property belonging to loyalists: Jean-Baptiste Tétrault dit Ducharme, Jean-Baptiste Tétreau, Timothée Tétreau, François Tétro son, Joseph Tétro son and Toussaint Tétro father.

Outcome

In 1839, Lord Durham submitted his famous report in which he affirmed that the Canadians were a people devoid of history or literature who had not accepted their defeat (that of 1760) and that they would be better off to assimilate them-selves in the great British nation. In any case, according to him, democracy would do it and immigration from the British Isles would end up making them a minority. He proposed a number of measures aimed at the assimilation of the French Canadians, measures that would be taken up again in the new constitution of the Act of Union of 1840.

The descendants of Louis Tétreau were in the heart of the action and seemed to have done well if not for the defeat of their movement. In this regard, the small number of combatants and their lack of equipment should be noted. Historians estimate that there was one firearm for between two to five men. Yet, it is to be noted that most of the demands formulated in the 92 Resolutions have today been realized. These include government responsible to the Chamber, control of public funds by the Legislative Assembly, proportional representation of French Canadians in the political institutions of the province, laws protecting the French reality (at least in Quebec), the abolition of the senate (whereas the demand had been that their members be elected), etc. In spite of the fact that our head of state is the queen and that she has representatives in each of the Canadian provincial governments, their powers are nil. Finally, I believe we can be proud of the descendants of Louis Tétreau who risked their lives and at times comfortable life situations in the defense of their ideas. We can be proud of the heritage they left us. This coming May 18, at the national patriots' day, we will remember them.

Notes

1- The ministers must draft reports to the Legislative Assembly and must remain in the good graces of the elected delegates.

2- Militia drawn from British inhabitants of Lower Canada living along the American boundary.

3- Persons and institutions who remained loyal to the British crown.

Sources

Alain Messier (2002). Dictionnaire encyclopédique et historique des patriotes (1837-1838), Guérin, Montréal, 497 p.

Jacques Lacoursière, Jean Provencher et Denis Vaugeois (2000). Canada—Québec (1534-2000), Septentrion, Québec 591 p.